Yet another incredible review by The Cage, this time our album Blown Away.

“Hovercraft proves with Blown Away that time only sharpens real music, it never dulls it.”

“Hovercraft doesn’t chase moments on Blown Away, they create them.”

“Blown Away proves that Hovercraft’s moment didn’t pass, it waited.”

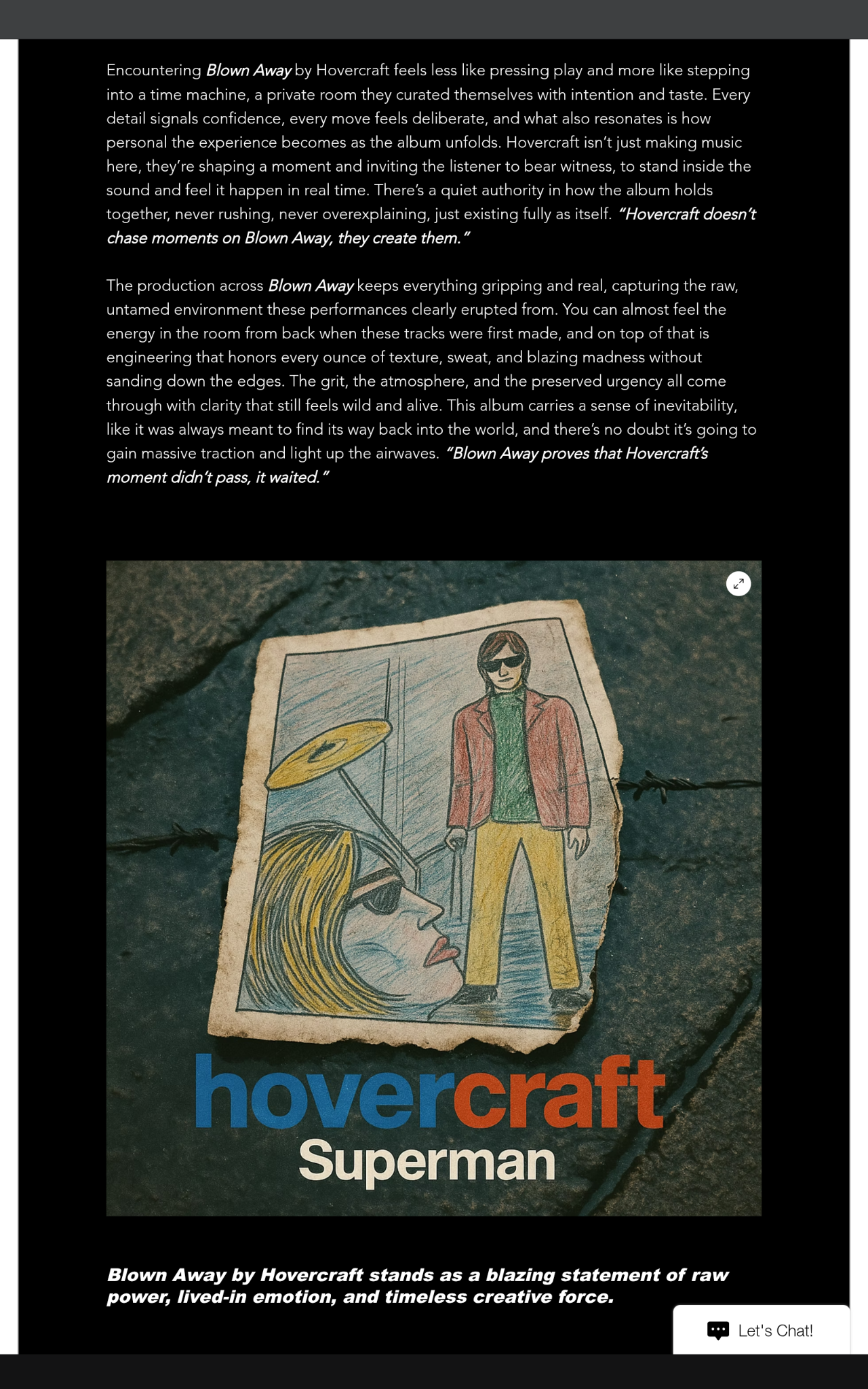

Blown Away by Hovercraft stands as a blazing statement of raw power, lived-in emotion, and timeless creative force.

Our friends at The Cage wrote wonderfully about New Pine Overcoat / Angel

“Hovercraft keeps finding new ways to make familiar feelings hit with startling force.”

“Angel proves Hovercraft knows exactly how to make vulnerability sound triumphant.”

“Hovercraft delivers the kind of release that reminds you why music matters.”

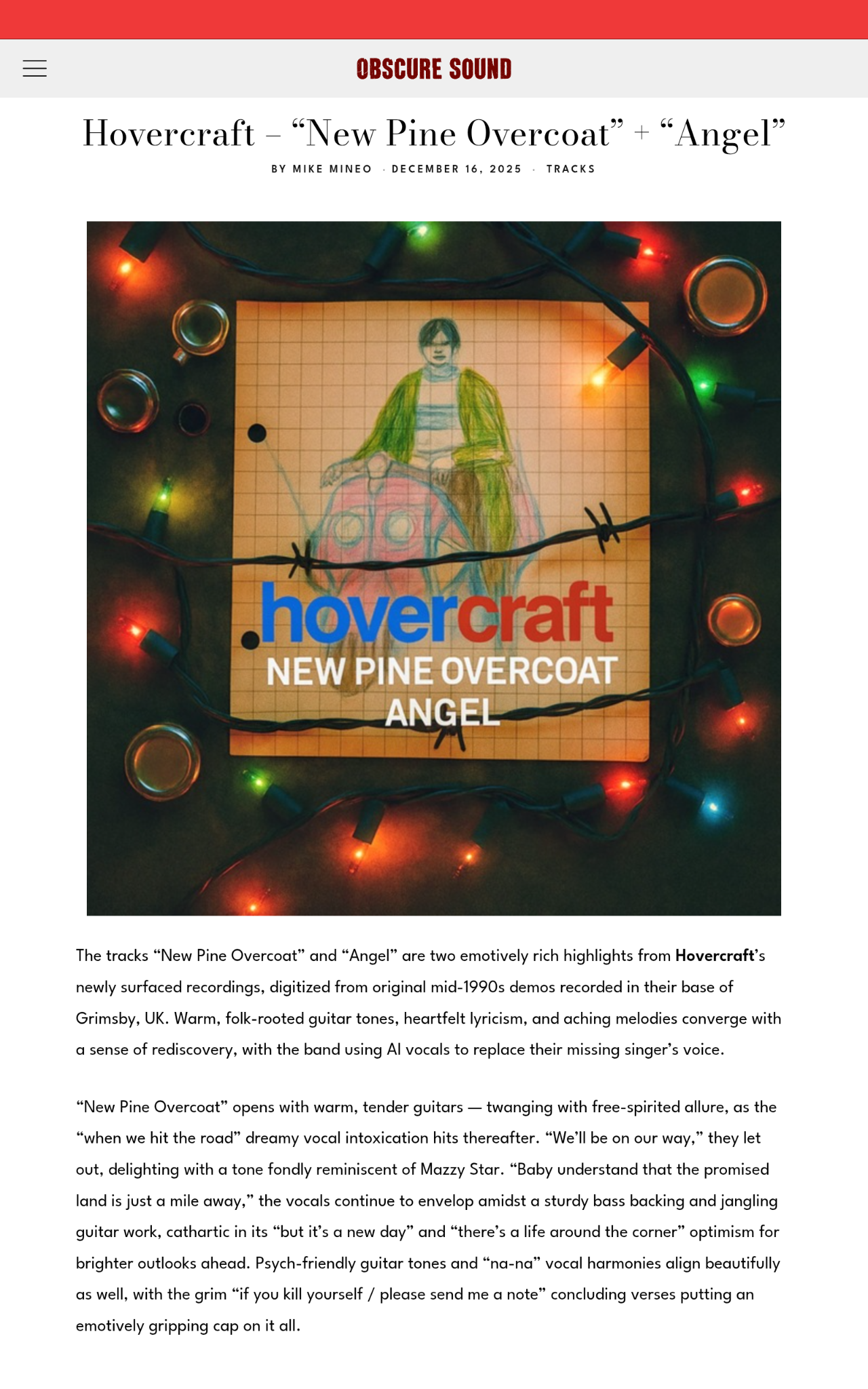

Mike Mineo over at Obscure Sounds reviewed New Pine Overcoat / Angel:

“…Warm, folk-rooted guitar tones… dreamy vocal intoxication… heartbreak-laden introspection”

Both these tracks are quality displays of songwriting and heartfelt emotion

Return Of Rock rocked Blown Away, describing it as:

“…a feral, heart-on-fire album…sounding impossibly alive…feels urgent in the way only real music does.”

‘Blown Away’ moves with remarkable focus. The sequencing feels intentional, drawing you deeper into its emotional gravity with each track.

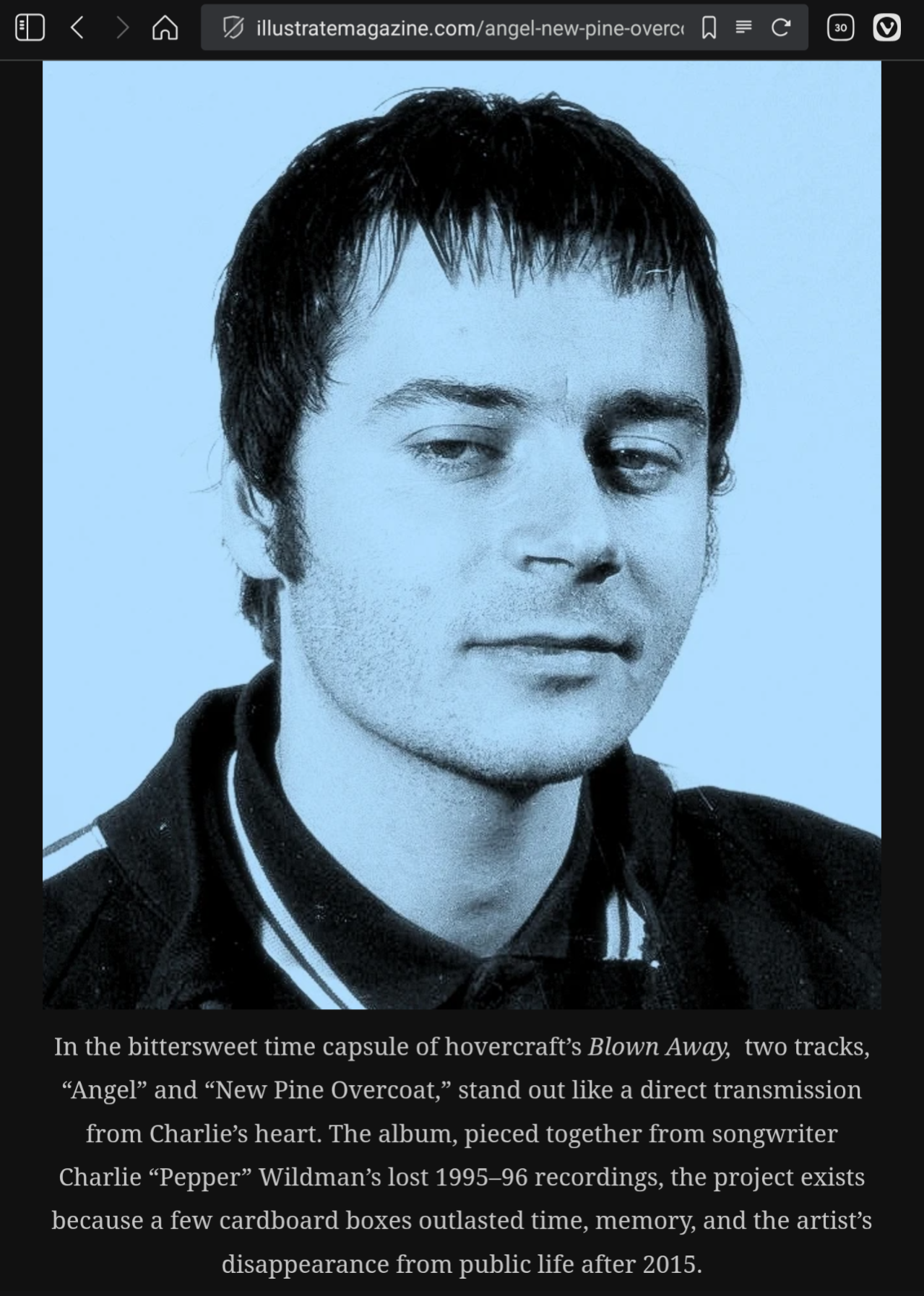

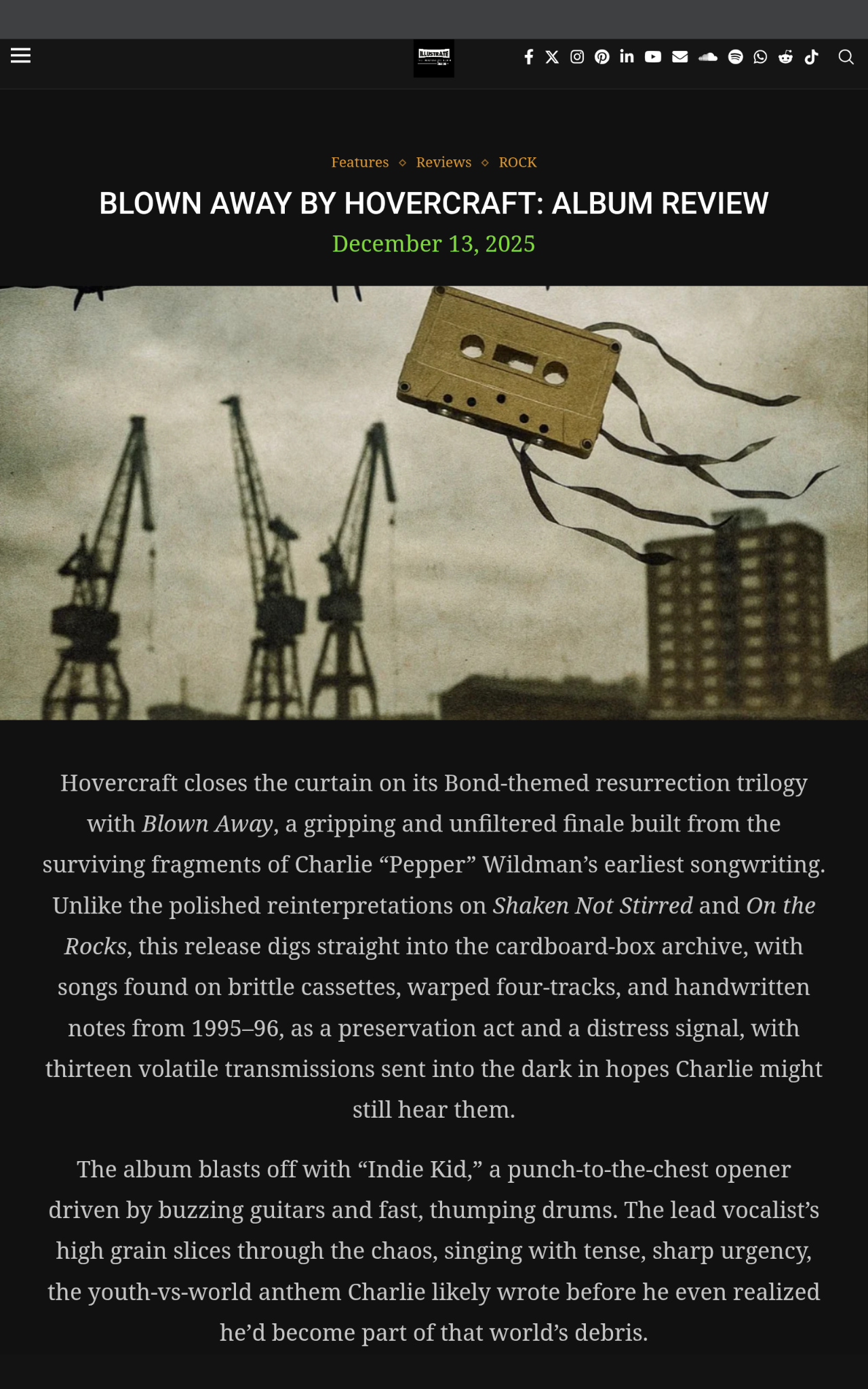

Illustrate Magazine reviewed New Pine Overcoat / Angel and Blown Away.

fragile art rescued from oblivion

a messy and vulnerable final flare shot into the void

A review of New Pine Overcoat at Lost In The Manor:

“…the messy and grand experience of being young”

The songwriting is pretty immaculate

New Pine Overcoat / Angel reviewed in Apricot Magazine:

“…like an apparition from the mid-90s… a drifting folk descent… a joke, a warning, a prophecy… a gentle unraveling”

subtle, poetic, and quietly devastating

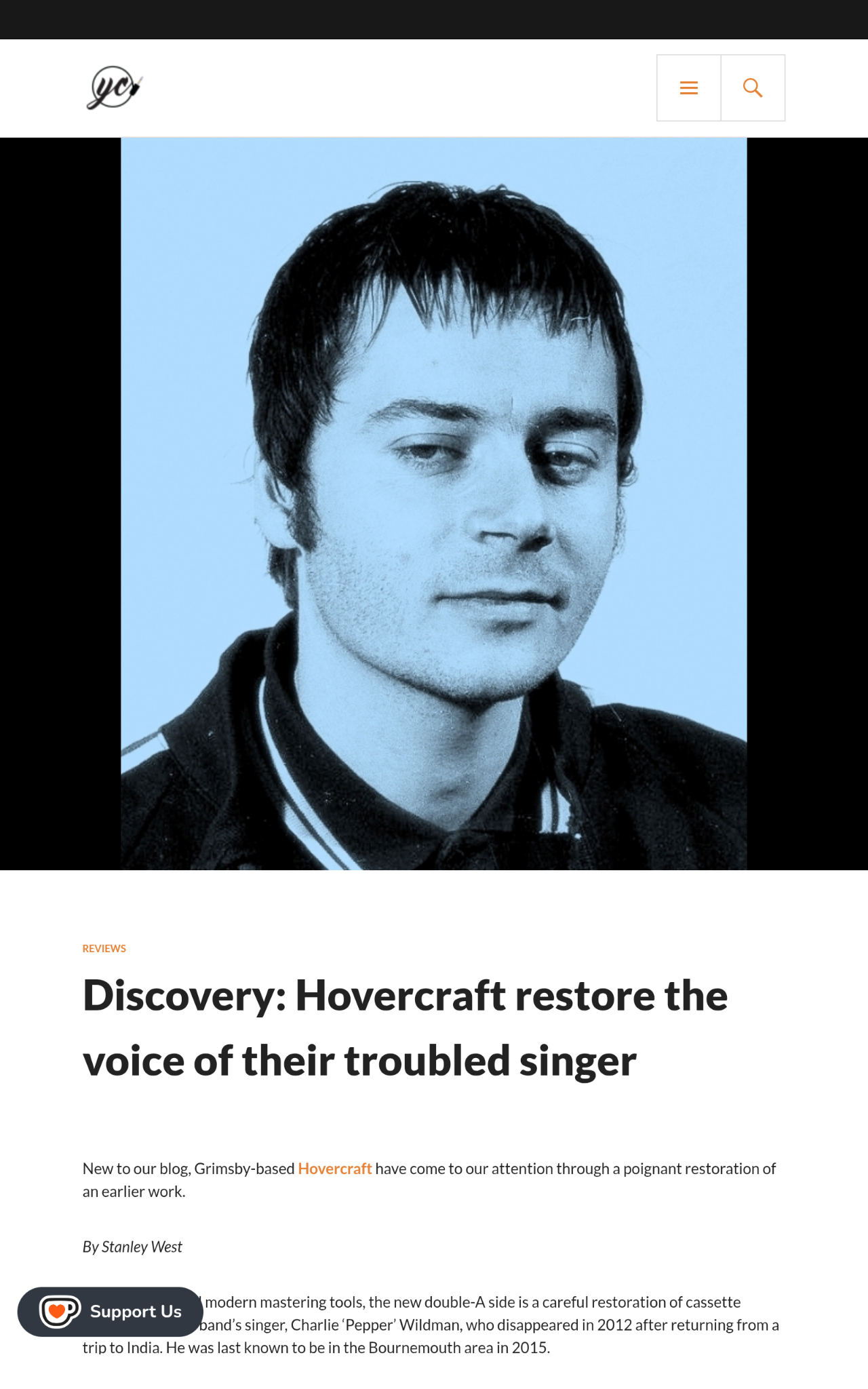

A little closer to Grimsby, Graeme Smith’s York Calling reviewed New Pine Overcoat / Angel.

…never stops sounding beautiful and sweet.

Absolutely incredible review of Blown Away by Dave Franklin at The Big Takeover.

“… these are great songs… raw, power-pop groove meets indie cool meets punky energy… Poetic, mystical, and marvellous.”

songs that should have been hits in any era of modern music.

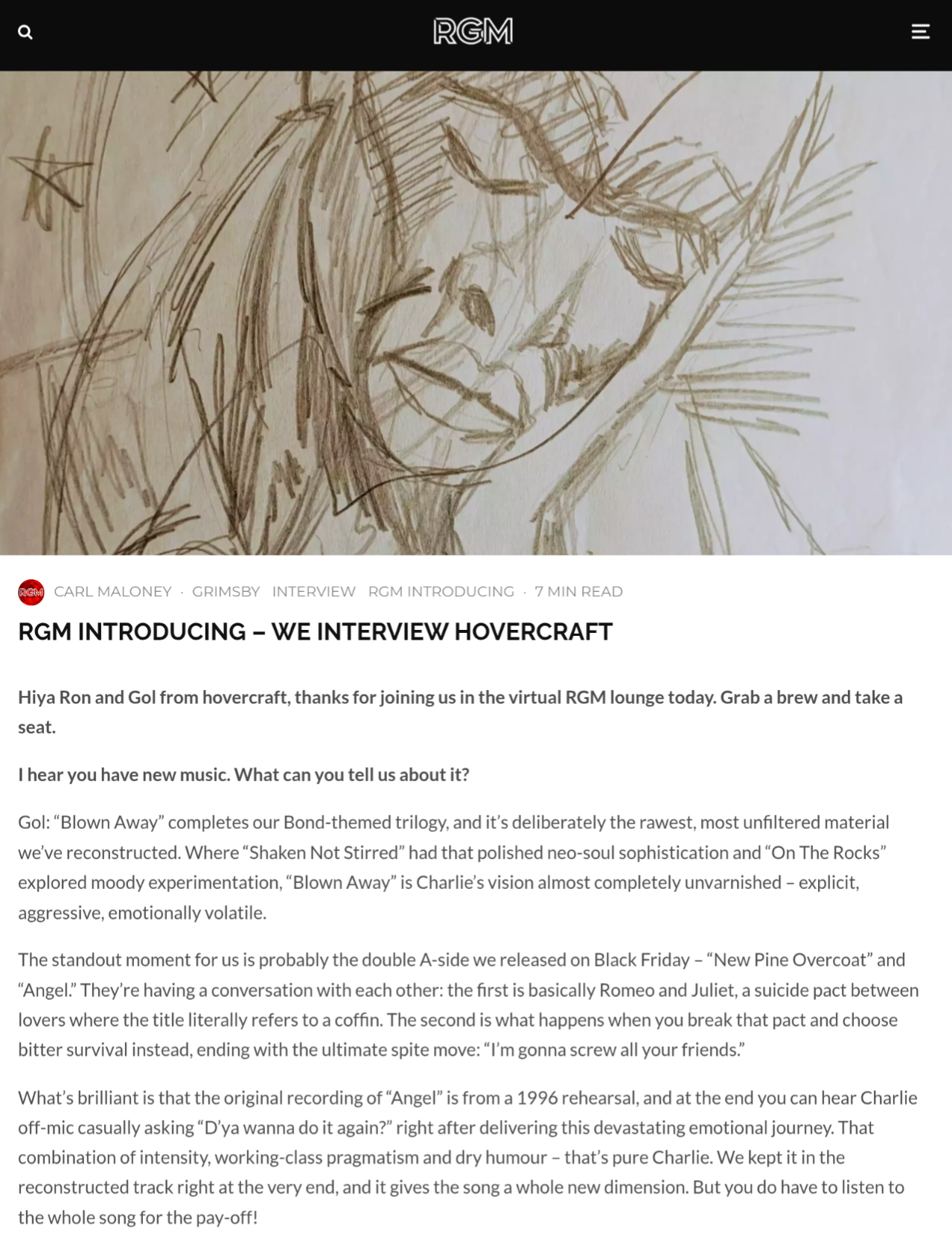

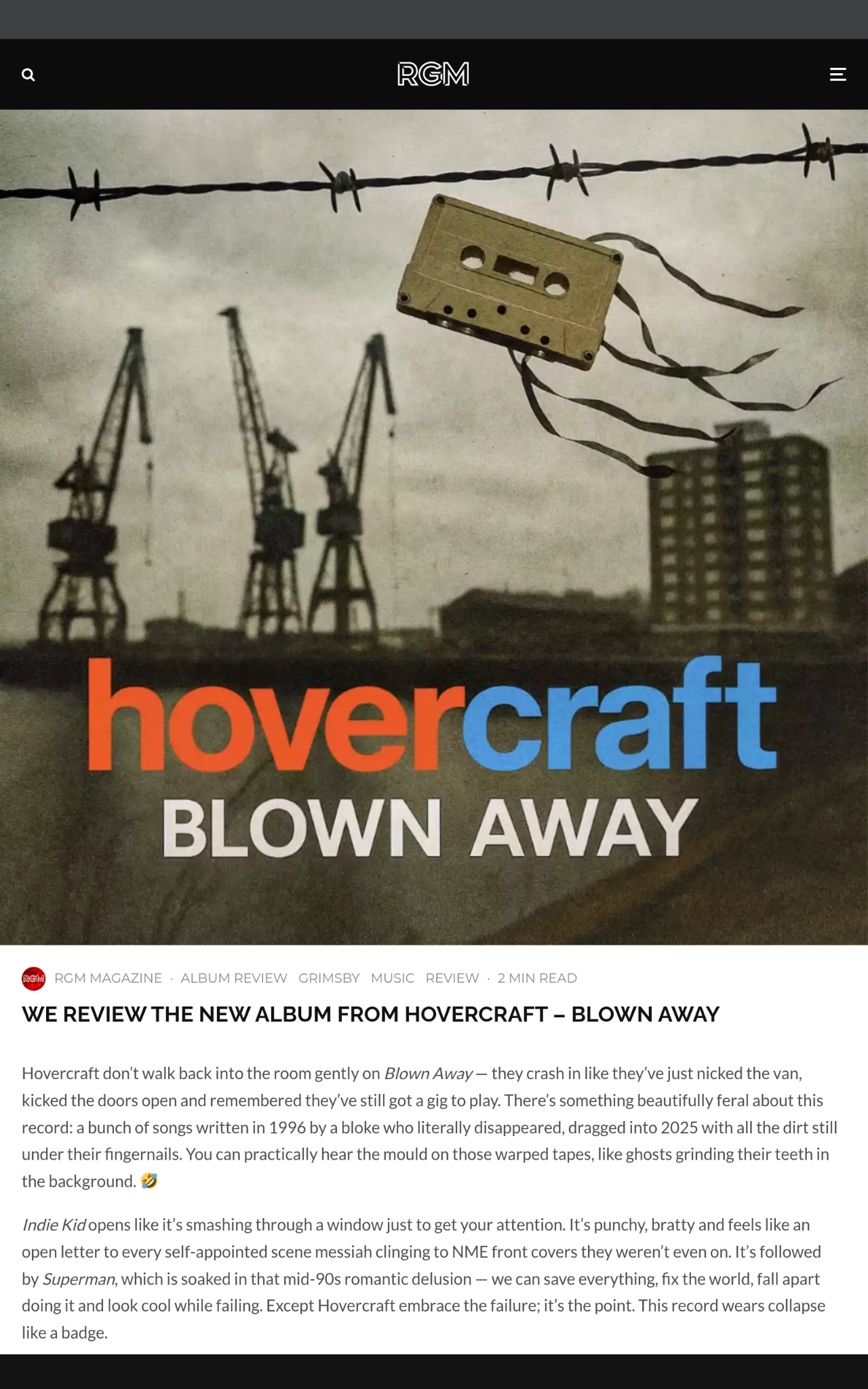

RGM (Reyt Good Music) interview and album review.

“The whole album traces that arc from hope to wreckage, sophistication to chaos. Like Britain itself, really. Like the hovercraft technology we’re named after…”

“…scrappy, unfiltered, and not remotely fussed if the edges slice your fingers… the most honest thing you’ve heard in years”

…messy, desperate and properly brilliant

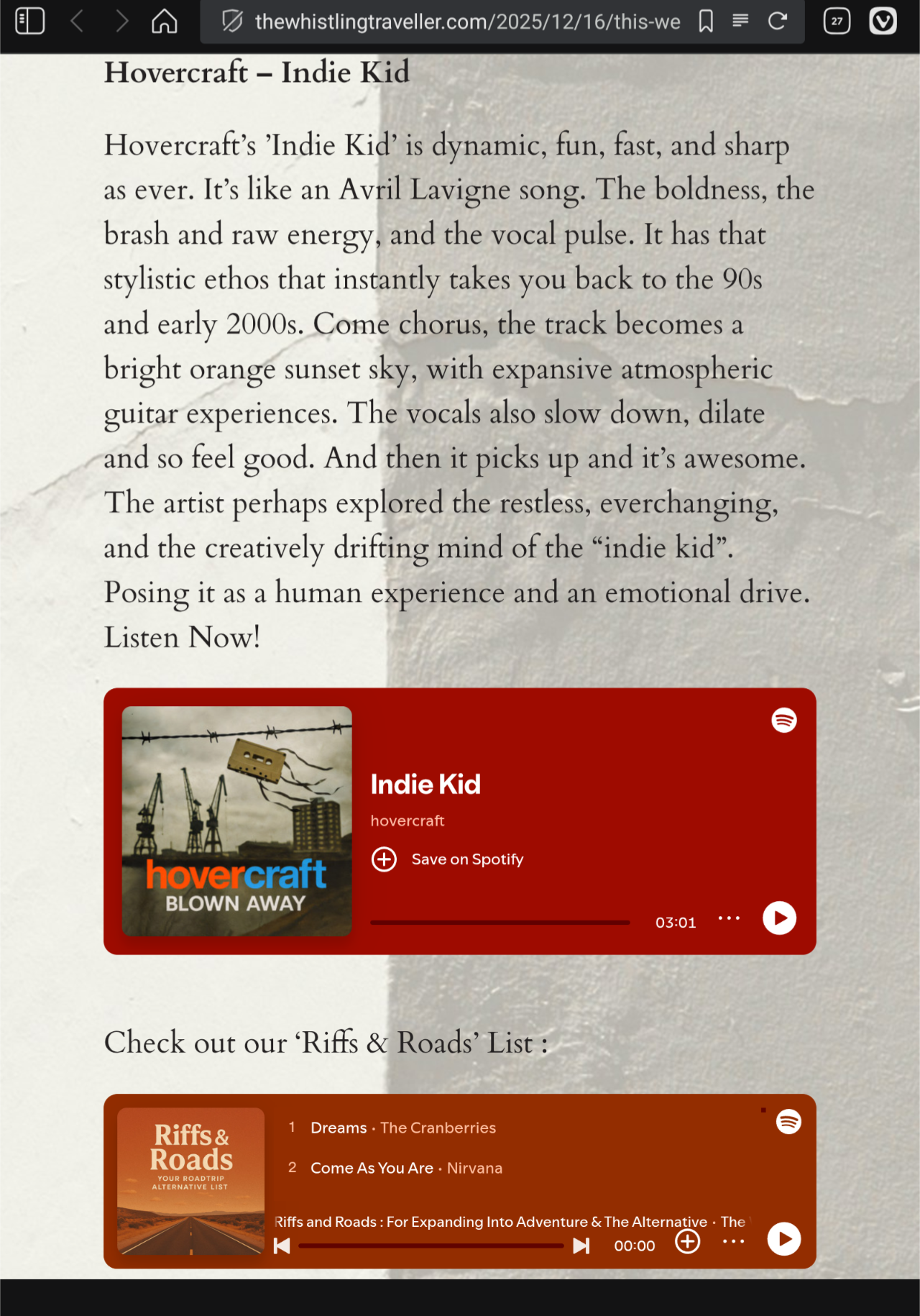

The Indie Grid reviews Blown Away.

“…These thirteen tracks roar with the youthful volatility… punk-blueprints and scrappy alt-rock skeletons held up to the light… what’s remarkable is how alive this record feels… the kind of track bands spend their whole careers chasing.”

a fever dream of defiance and collapse

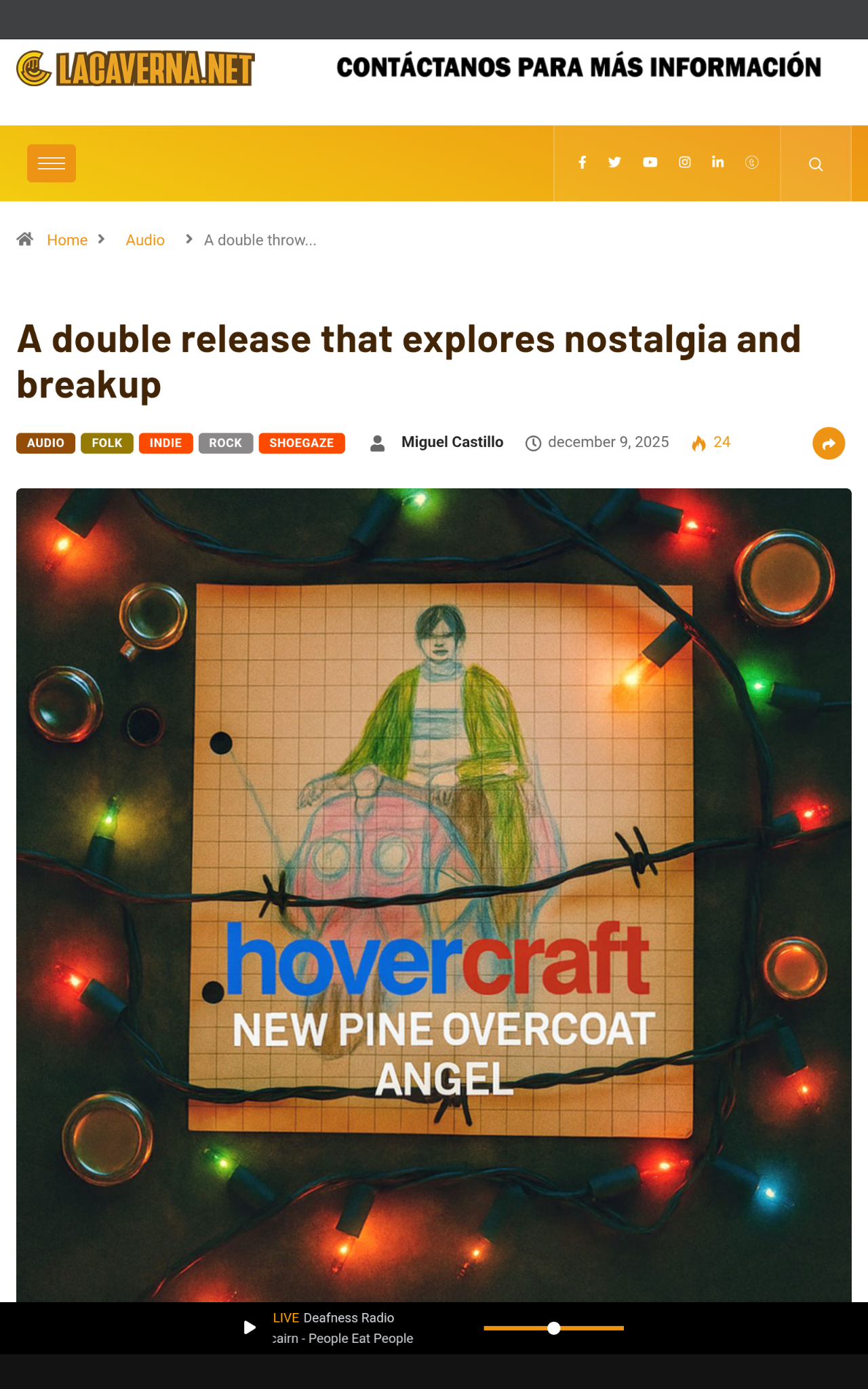

Big thanks to Miguel Castillo for his amazing reviews at La Caverna.

New Pine Overcoat / Angel: “…the spirit of a youth oscillating between idealism and fatalism….evoking a world where hope and exhaustion coexist…a devastating portrait of loss, dependency, and bitter resilience.”

…a double release that perfectly embodies its raw, emotional and deeply human aesthetic.

Blown Away: “…the fantasy of escaping reality while admitting the impossibility of sustaining a heroic facade….addictions, disenchantment, vulnerability and the desperate search for meaning.”

…an acidic portrait of British youth, drenched in endless nights and existential disorientation.

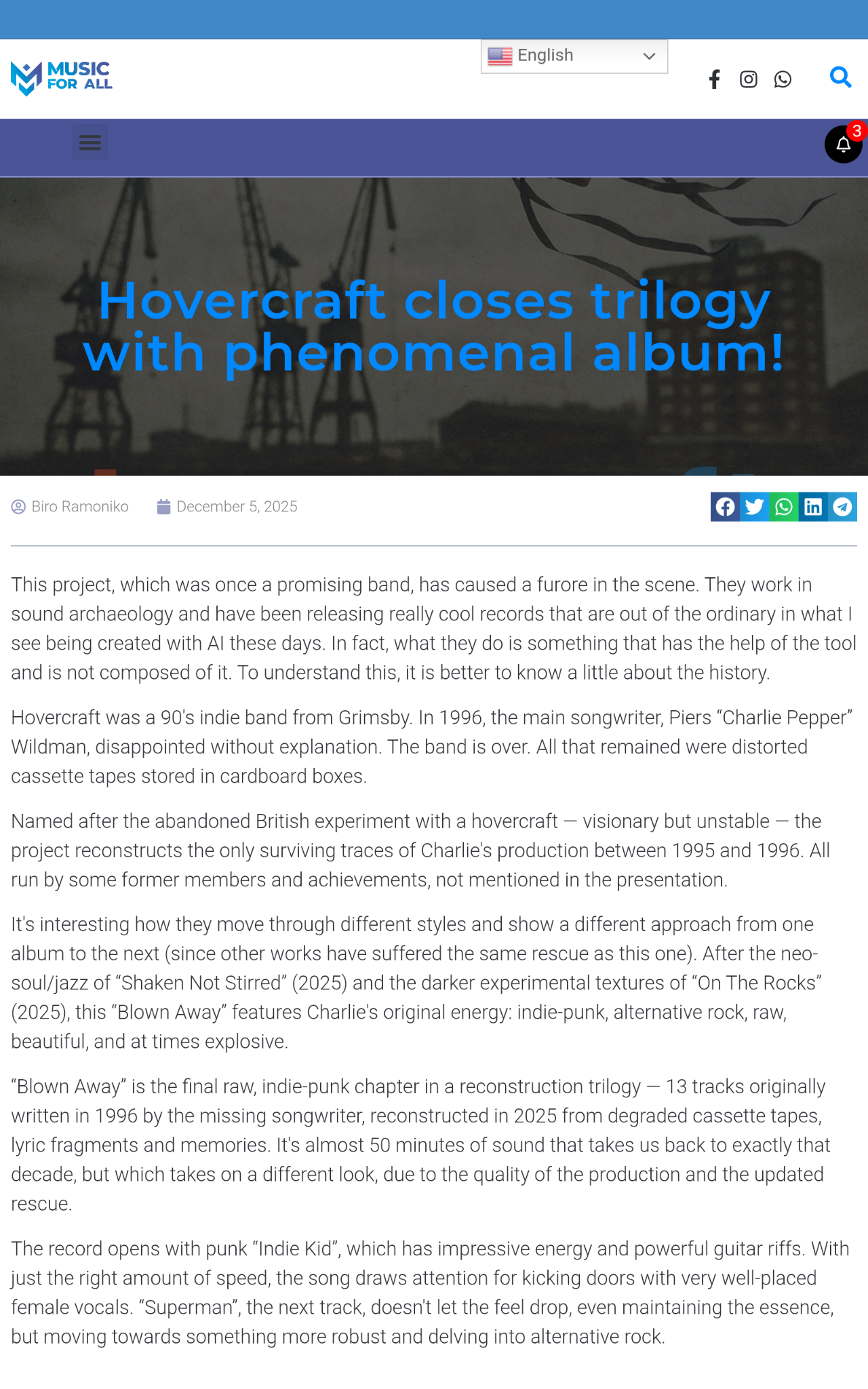

Another superlative review from the guys at Music For All!

Blown Away: “…a phenomenal album! A tracklist, incidentally, that has absolutely no decadent moments.

With just the right amount of speed (Charlie would love this one!)

What a fantastic review of Blown Away by Edgar Allen Poets!

“…restless, stylish, and driven by a desire to move… mix of nostalgia and adrenaline… the band proves they’re unafraid to take stylistic risks… dreamy but grounded, hazy but intentional… The groove is infectious…”

Every track contributes something distinct, and together they form a journey that keeps you locked in until the closing note.

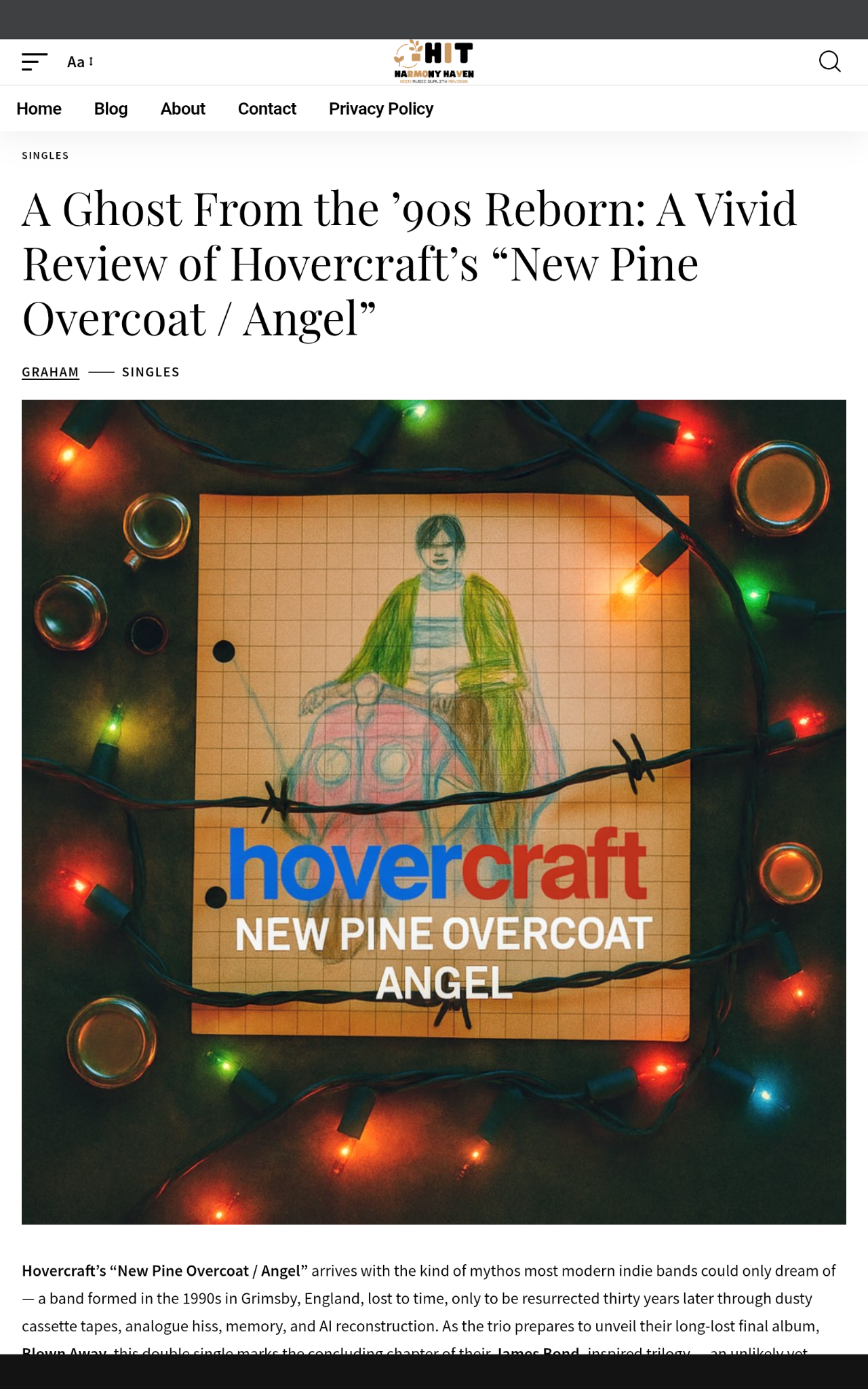

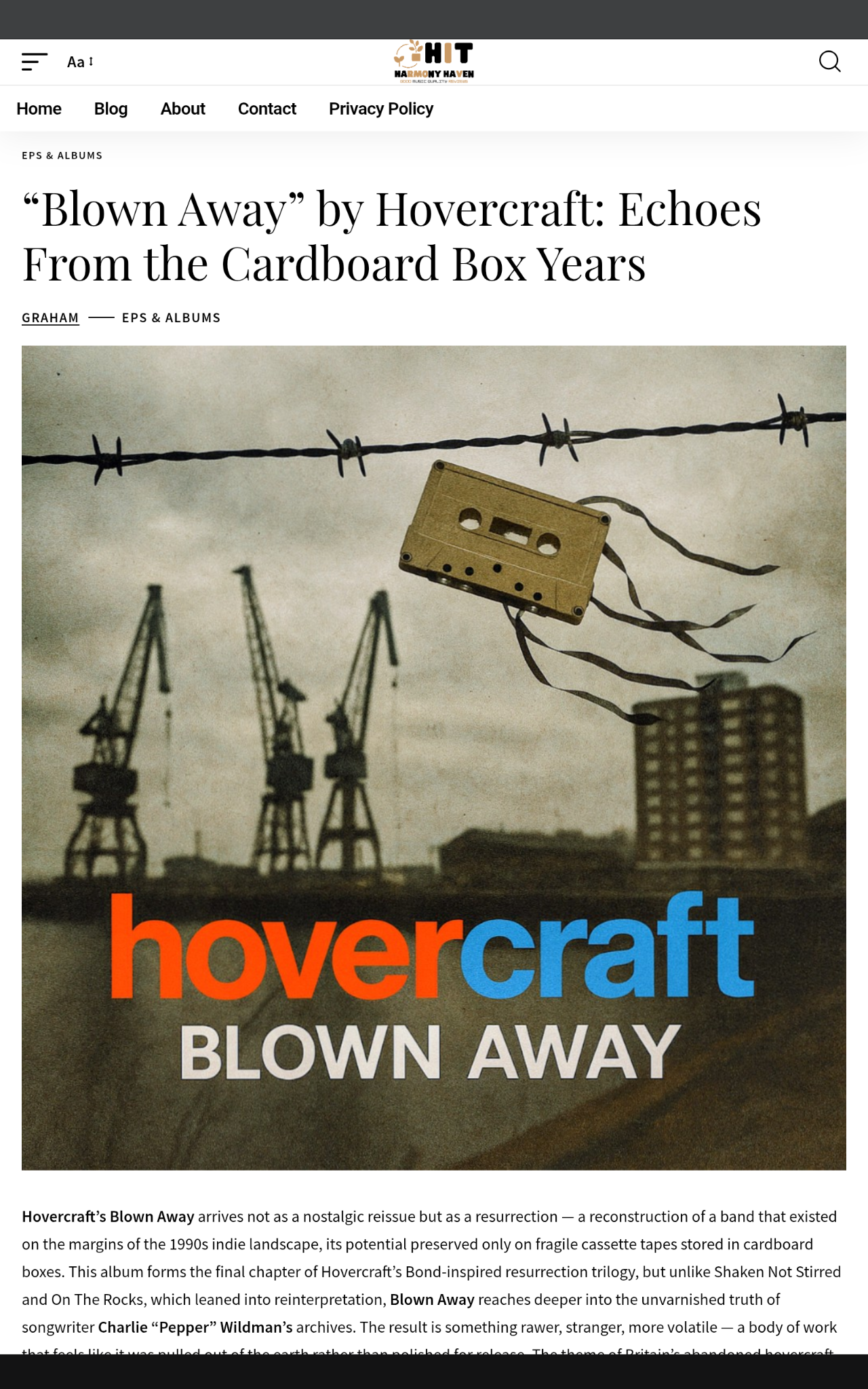

A couple of really terrific reviews over at Hit Harmony Haven.

New Pine Overcoat/ Angel: “…raw, human, and unmistakably real… the kind of lyric Britpop could have produced but rarely did… ahead of its time… an emotional arc that feels less like a demo reconstruction and more like a cinematic short film.”

Hovercraft’s revival is not simply nostalgic, but restorative. It bridges time, technology, memory, and grief, turning the act of musical resurrection into an artistic statement of its own.

And Blown Away: “…an emotional excavation… stylish, restless, and subtly melancholic beneath the adrenaline… swagger laid over vulnerability, noise layered over doubt… hypnotic soundscapes… a unique dream-blues sensibility.”

Hovercraft presents not the polished fantasy of what the band could have been, but the flawed, brilliant, beating heart of what it was.

Our friends at Sinusoidal in India reviewed New Pine Overcoat / Angel and Blown Away.

a chance to face the pain, instead of running away from it.

Songwriting, with purpose

Dave Franklin reviewed New Pine Overcoat (“brilliantly mercurial”) and Angel (“wonderfully not quite what it seems”) at The Big Takeover.

What would the Hovercraft story have been had they gone the distance? What would the modern popscape look like today if things had been different? We can only imagine.

Fred Bambridge at It’s All Indie described New Pine Overcoat as “mesmerising” and was “astounded that [Angel] is a 30-year-old track.”

I just feel bad as if this came out in the 90s I honestly feel like the whole world would know about Hovercraft.

Another lyrical and evocative review from our Brazilian friends at Music For All.

Shake, rattle and roll?

There’s plenty of hiss on the old original tape audio from which this new version was created, and you can certainly hear Mr Shimble rattling around on his drum kit. An alternative translation might be: “The track is supported by the ride cymbal’s consistent shimmer (which gives it that raw lo-fi texture) and the snare’s rhythmic rattle, while the sweet fragile female vocal fills the lyrical space, graced by a careful but sufficient bassline.”